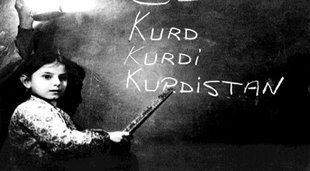

Kurdish Culture as an Example

It is widely believed that culture is created but language is partly innate and to a certain extent, instinctive. They are both developed through the journey of life and have different and open areas of study. Cultural differences and language variations also play a significant role in bringing about other meanings of the same word or expression. That is the reason why our understanding of them may contradict or assimilate.

There are certain stages of life that require an appropriate use of language and that tell us that the effects of society on language cannot be neglected. Language does not constrain people’s ability to think as sometimes people claim that they cannot express what they feel or think. It rather reflects personal perceptions and cultural preoccupations.

If thought is controlled through cultural taboos, there would be fewer words in the language to express an action or event. Cultural inhibitors concerning what is proper and improper to talk about has has caused the strength of the subject to grow exponentially, hence, narrowing the range of thought. As a result, when a Kurd talks about sex, they refer to the action indirectly; for example, “they are/were in bed together”. Needless to say, this sentence deals with association, and does not quite match with sex, which is established in English culture.

In addition, there are some other phrases relating to sex but most of them are very degrading and shameful in the sense that they are never used by a Kurdish-educated speaker in public gatherings or when giving a speech. From my experience, those degrading expressions are not documented in Kurdish dictionaries. They are mostly used in oral communication.

This restriction on language, which is caused by culture, does not mean the Kurdish language is not inspirational or does not have the ability to find words for such things or that other languages are richer. Kurdish society is known for its strong family relations and hospitality. In the English language, there is only one word with which a boy can call his mother’s brother or father’s brother which is ‘uncle’. In Kurdish there are two separate words for ‘uncle’.

Kurdish people have been oppressed and our lands have been occupied throughout history and that has hugely affected our psychology and culture of communication and increased the number of words that are used to describe hardship. In addition to this, a Kurdish nationalistic journalist would use “Peshmarga’’ instead of guerrilla, militia or freedom fighter because the Peshmarga’s portrait has a magnificent position in the memory of the Kurds and when it is translated to a non-Kurd, it leaves no room for other meanings or interpolation. Consequently, the journalist’s reputation will be preserved and his patriotic devotion will not be questioned.

It has to be noted that we can still understand certain types of cultural norms and traditions without knowing the language. If you happen to come to South Kurdistan on March 21st of every year, you will notice that almost everyone is wearing Kurdish traditional clothes; keep in mind that it is a national day and celebrated in almost every home.

Some cultural practices need to be preserved, while others need to be adjusted. For example, the Kurdish language has a number of exclusive proverbs. When they are translated into other languages, they convey prejudiced attitudes in favor of men. “If rain falls his mill works, if it does not fall his plow works”, this is a widespread translation of “baran bbaret ashi degerit, baran nabaret juti degeret”. Even if “his” is used unintentionally or as a general pronoun, it portrays or rather narrows adult human beings as a source of a physical power that solves problems. Kurdish women have worked shoulder to shoulder in farms and gardens and they even fought in the mountains of Kurdistan as Peshmargas and played a huge role in establishing the Iraqi Kurdistan Region.

Some words will fade away with the passing of time and others will be replaced. Kurdish people expect to be greeted with a handshake and a warm reception, while Americans may be satisfied with a smile. In face-to-face greetings, a Kurd mostly asks questions and tends to forget the answer. Consider the following:

A: How are you?

B: How are you? How is your family? How is your health?

A: How is everyone? How are your parents? How are your wife and children?

After asking each other many questions, they will then come to answer the questions. When asking an American “How are you?” s/he would normally say, “I am fine. Thank you. How are you?” Such language use is influenced by culture and could bear many interpretations. Kurdish people generally may be described as people-centered, friendly and truly want to engage into the conversation and appeal to the listener’s emotions. By contrast, they may be described as chatty by a foreigner. An American might be accused of being unsociable or insensitive by a Kurd. Nevertheless, the same American may be described as direct and to the point by a Kurd who has information about American culture. Culture and cultural knowledge here determines the way our language is observed and used.

After all, humans are endowed with the ability to speak but they learn cultural conventions through imitation and cultural rules. To address sensitive subjects, there seems to be a need to use several words to represent one action or concept. But that does not necessarily impose curbs on the proliferation and growth of Kurdish vocabulary, dictionary, and language.

To conclude, Kurdish language is not free of its cultural influence but with the current technological revolution and the expansion of media, the Kurdish language will surely adopt, embrace, and has the flexibility to absorb new words and there seems to be no cultural frontier when it comes to the Internet.