Women of Kurdistan

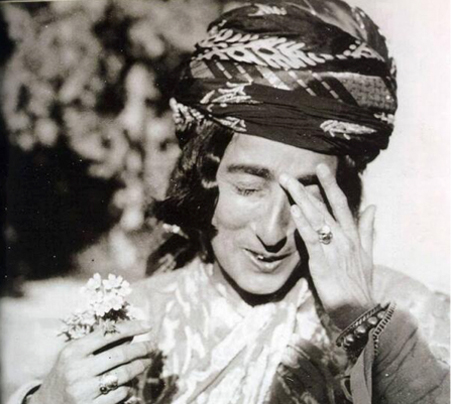

– Hepse Xanî Neqîb (1891-1953)

‘I’m proud to be a woman, and especially a Kurdish one, there is no difference between men and women, so I am going to continue’ – Hepse Xanî Neqîb

We have been hearing and seeing a lot about the ‘Kurdish Female Fighters’ in media all over the world this past year as the fighting against the so called Islamic State intensified. As Kurds, we can’t help to be admired and feel a sense of pride over these women, as young and elderly take up arms to help protect their homes and families. Though the Kurdish female fighters got the world’s attention just in this resent year, the tradition of women joining men on the battlefield have a long history within the Kurdish community. Greco-Roman historian Plutarch reported local people in what is now northern and western Kurdistan fiercely defending their home from the invading Roman troops in the 1st century BC. The Kurdish Zand-dynasty of 1750 AD were ridiculed by the invading Afghan forces, accusing them of “hiding behind their women’s skirts” because the founder of the dynasty, Muhamed Karim Khan, fully adhered to his ancient Kurdish costume: he and his soldiers enjoyed the military support of their brides, who fought alongside them as they routed Afghan forces.

The last ruler of an important medieval Kurdish Daylamite dynasty, the Buwayhids of Ray, modern day Tehran, was a woman, Sayida Mama Khatun.

For nearly 30 years she safeguarded the kingdom from the onslaught of the Turkic nomads and their mighty Ghaznavid king through a combination of courage, wit, and diplomacy. Years later the Ottoman and Russian forces had to deal with women such as, Mama Maryam, Mama Pura Halima of Pijdar, Mama Kara Nergiz of the Shwan tribes of central Kurdistan, as well as Mama Persheng of the populous Milan tribe of western Kurdistan, all fighting to preserve their autonomy in their mountainous homeland.

At the same time it was not unusual for a Kurdish women to rule towns, cities or even tribes in the past, it’s important to not forget the patriarchy and conservatism that permeate the Kurdish society of today. We are aware of Kurdish Female fighters and their history but what do we know about the women who instead of a weapon used the pen to fight for their people, homeland and the right to exist. One woman who did just that that but sadly has ended up in the shadows of history is Hapsa Khani Naqeb.

Hapsa Khani Naqeb was born into a prominent family in Silêmanî (Suleymaniya) in 1891. She was the daughter of Sheikh Marif and Salma Khan. Equal to the reputation of her parents, Hapsa Khan was known for her generosity and charity work at a very early age. She possessed a special place for those women who became victims of injustice and social cruelty, particularly in the city of Silêmanî and it’s surroundings. She played a major role in establishing the first school for girls in Silêmanî in 1926 by going from house to house with the teachers to register as many girls as possible, and to even convince parents to send their daughters to school. If a family’s economy were not sufficient to support their daughter’s education, Hapsa Khan would then personally help with the financing. Many girls, and boys, got a chance to go to school thanks to her. Many admired Hapsa Khan and for that reason her visitors ranged from writers, artists, poets and men of high rank. In the book ‘Kurdistan: in the shadows of history ‘, the German photographer Lotte Errell describes Hapsa Khan as the woman “whose husband gets up when she enters the room”. Hapsa Khan loved to help. A man from Baghdad once visited her and the man said that he wanted to write a book about the history of Iraq. As soon as the man had explained his idea she hurried to get a pair of scissors to cut loose five gold coins from her Kurdish headdress. She gave the gold coins to the Iraqi writer and offered her full support for the project.

Her house soon became a centre for women where they were learning high social morals to a national sentiment. They also discussed the role of women in society and national rights for Kurds, how to achieve freedom for the people. Her home became a place where women could turn to if they ever needed help. Her house was always open to the poor and she never treated people differently based on their background. There are many stories about Hapsa Khan were she bought clothes or offered meals to less fortuned people. She would do what ever she could to help people in need. Once when Hapsa Khan was visiting Qarax she met an old man sitting with a girl in his arms and another girl crying next to him. She approached them and asked what the problem was. The old man was from eastern Kurdistan (‘Iran’) and her daughter was very sick but the man did not have enough money to reach Kirkuk in time. Hapsa Khan invited them to dinner and made sure to arrange a caravan to take the father and the daughters to Kirkuk in the very same day. Hapsa Khan won the trust of the people when she helped save the lives of many girls who were sold or taken to Baghdad because of poverty between the early 1930’s, by doing all she could in her power to reunite the girls with their families again. It’s said that she even helped one of the girls to get married and paid for the whole wedding herself. Speaking of weddings, she also helped to mediate between the families of a Christian girl and a Muslim boy who had fallen in love with each other and wanted to get married.

Hapsa Khan was also active in politics. She was active during Sheikh Mahmud’s revolt against the British forces in the early 1920’s. She and her sister contributed financially to the Kurdish resistance movement and they also encourage people to join the resistance and helped organize demonstrations in the city of Silêmanî. When Silêmanî were being bombarded and later evacuated by order of the British in the early 1920’s, Hapsa Khan refused to leave the city and instead stayed with the families who could not escape. She luckily survived the bombings and war and in 1930 she sent a political letter to the ‘League of Nations’, calling for rights for the Kurdish people within the framework of Kurdistan. Later when Qazi Mihamed founded the Kurdistan Republic of Mahabad in eastern Kurdistan during 1946, she showed her full support for the Republic. She also established what is considered the first Kurdish women’s rights organization (Kurdish Women’s Association) in Iraqi Kurdistan in 1930 to solve issues related to women and offer them financial support. The association defended the rights of women at the beginning of the last century in the Middle East.

“If she had been a man, she would have been a strong challenge” – Sheikh Mahmud

It is obvious that Hapsa Khan had a strong character and did not hesitate to fight for what she believed in. She was not only the first woman in Silêmanî to inter the cinema, but she is also believed to be the first woman who stressed the importance of education for women to gain their freedom. She is the reason why my grandmother, born in 1929, was able to go to school and learn what many girls take for granted today: to be able to read and write. Women like Hapsa Khan should have a special place in our history books and hopefully her legacy and work can become a source of inspiration for future generations. Hapsa Khani Naqeb passed away on April 12th, 1953. After her death in 1953, her home, as she had intended, became a school.