Teaching should go beyond giving advice. Teachers, as well as giving guidance, should provide a warm, encouraging, comfortable environment where humor, supportive feedback, lesson planning, regular meeting with parents, and checking progress are the most palpable features of their teaching methods.

Subsequently, the teacher can tailor the development and highlight the important activities that are required from students and facilitate a smooth and effective teaching environment. Conversely, when school life becomes hostile and academic demands become increasingly demanding, the education process will be affected, teaching may become boring, and learning is compromised.

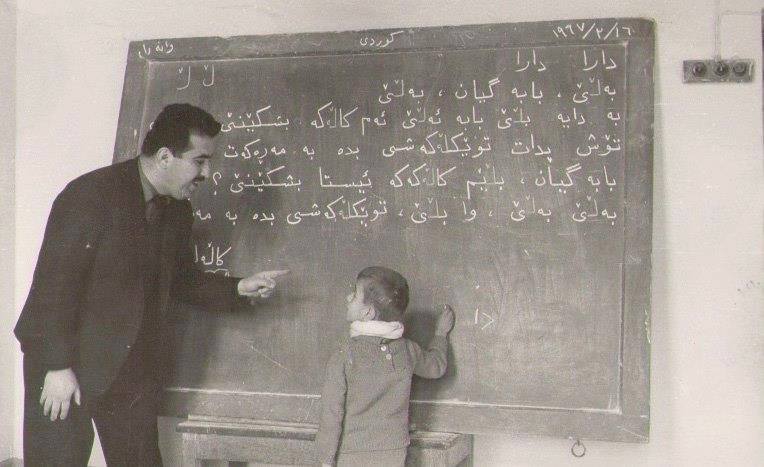

Teaching in a specific context and environment is bound with its culture. ‘Mamosta’ is the translation of ‘Teacher’. Mamosta is one of the most frequently used words in Kurdish culture, often used to refer to people who are not even teachers. So, when a Kurd calls you and says ‘Mamosta’, do not be surprised. Related to this is: when you want to call a Kurdish child but you do not know his name, just say “Hama (gyan)”. Interestingly, Kurdish teachers say “Hama”, when they forget a male student’s name. Language in this precise context reveals cultural codes, codes that are easily recognized by Kurdish students.

If we do not know a man’s name or have forgotten his name, we just simply call him ‘Mamosta’ to make him feel respected thereby avoiding any sort of embarrassment. When a man performs a good job, we call him ‘Mamosta’. There is a kind of greatness, admiration and love attached to it. Conversely and even ironically, when a boastful man attempts, without success, to philosophize, we say “he has made himself a philosophy teacher’’.

Mamosta has a huge role in Kurdish society; that is why we call scientists, artists, sports coaches, members of parliament, retired engineers, archeologists, poets, philosophers and doctors Mamosta, if we cannot recall what their real names or jobs are. I have actually seen people, in my hometown, addressing a tea-server in this way. Interestingly, both are my acquaintances. The use of ‘teacher’ in this specific context is not to look down upon his job, rather to pay more respect for the kind of job he is doing.

In Eastern culture, a university professor is called professor, while a professor can be called a ‘teacher’ in Kurdistan. We never, for example say Professor John, we just say ‘teacher’ when we call John. Culture here mirrors social reality- but that does not mean that cultures do not have elements in common.

Every job needs a good amount of skill, desire, knowledge, preparation, motivation, and challenge to be successful. A teacher’s responsibility and profession, by nature, requires many sociable skills to adapt themselves to different types of opinions.

Teachers are expected to encourage students to foster their developments and give them opportunities to creative analysis and share ideas. Likewise, teachers have to maintain and monitor students’ interest and progress. When a teacher, for example, fails to adequately begin and end a lesson, lacks feedback, does not know how to keep the students busy, fails to set up group work activities, the classroom climate can lead to total chaos, vandalism and cheating.

Related to this was an incident that I was told by a friend. He said that in one of his classes, in order to force the students to remain silent, he would give a piece of chalk to the quietest student. Later, I discovered, such deceptive techniques was typical of him. The teacher creates a certain symbol that is understandable to the culture I belong to. I went through the same experience as a student.

Another general characteristic of Kurdish teachers, be it a Basic School teacher, High School teacher or University teacher, is that society expects them to know everything, from playing video games to politics, when asked a question.

Our expectations of teachers are high and that is the reason for our great admiration. The high expectation and admiration has a historical root. Kurdish teachers are more sociable compared to other officeholders. This facilitates more interaction between the parents’ students and the teachers. The parents will get the message that their thoughts are of great value; therefore, they take part in the process and are held accountable for the students’ progress.

School and university are complex social establishments. Students and teachers can build lifelong friendship, find special friends, share interests and worries, relate and apply literature and science to real life. Conversely, they may be bullied, stressed, threatened, despised- but these aspects will turn into lessons, lessons that can establish your own well-being and self-esteem upon.

In conclusion, teaching varies from culture to culture, teacher to teacher, lesson to lesson; class to class. In order to foster enjoyment, advocate mutual trust, maintain positive motivation, preserve active involvement, sustain moral and cultural development, teachers in general and Kurdish teachers in particular should update their teaching methods; get rid of certain techniques and embrace new strategies and that can best be done through small-group discussions, pair work, scientific trips, visiting museums and historical places, use of cards and worksheets, overhead projectors and computer packages- which did not exist two decades ago, in the 1990s.