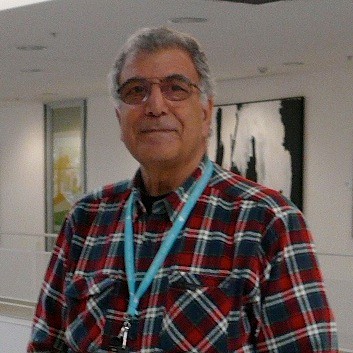

Kak Shahin was born in the village of Mezre, in the Kurdish region near the town of Kobani at the border between Syria and Turkey in 1946. He left for Europe to study in 1965 and arrived in Sydney from Munich on 29 October 1968 where he met his wife Robyn Hyde while working for MAN DIESEL in Kurri Kurri, NSW. He then married in 1971 and now has two wonderful sons, Che and Shahn.

Kak Shahin graduated from Macquarie University in NSW at the end of 1977 (BA, Dip.Ed.), he later acquired further qualifications in journalism, the teaching of German and broadcasting. He was employed by the NSW Department of Education and Training as a teacher, consultant and in other positions from 1978 till the end of 2004 when he officially retired.

The first radio program he presented in Sydney was a weekly Kurdish/English program on 2SER FM: 1982-83. In 1984 he started the Kurdish Program on Radio 2EA. This program continues at SBS Radio today presenting two one hourly programs a week.

Many of his articles, poems and short stories are published under the name Shahin B Sorekli in both Kurdish and English, while some others in English under the name Chahin Baker. His Kurdish writings (Kurmanji), including 9 books, were published under the name Şahînê Bekirê Soreklî.

Kak Shahin has been involved in Kurdish politics since his teens and was the president/secretary of the first Kurdish Association in Australia from 1979 till about 1984. I had the pleasure of meeting Kak Shahin earlier this year at an Australian-Kurdish conference where he presented his emotional and passionate presentation on his own journey and the history of the Kurdish community in Australia is one that will stay with me for a long time. He is full of wisdom and can inspire a generation into action, I hope this small insight into this brilliant Kurdish academic will inspire many more.

Why and how did you get involved in Radio work?

When I was at Macquarie University I was one of the contributors to a program in English that supported the Palestinian cause and was run by Australian and Palestinian friends. My contribution was mainly related to may background and the Kurdish issue. The program was presented on the educational radio station 2SER that was one of the first FM stations in Sydney. With the help of some Kurdish friends we bought the right to broadcast a 30-minute program a week. That was the start.

After a long effort we were able to get a place for the Kurdish language on 2EA that was known at the time as an “ethnic radio.” I started with a trial program in August 1984, I believe, that turned into a 30 minute a week regular program. In 1993, when SBS moved to Artarmon in north Sydney, the Kurdish Language Program became an hour a week program and was now reaching Melbourne as well. Currently our program broadcasts on Fridays (6.00-7.00 PM) and Sundays (2.00-3.00 PM). The Sunday program is a national program, i.e. it reaches all Australian major towns: (www.sbs.com.au/Kurdish)

I chose to broadcast in Kurdish because of my love for my mother tongue and because the Kurdish language was oppressed and we had no radio in Kurdish where I came from. I also hoped it would benefit the Kurds in Australia and contribute to establishing a united community.

What advice would you have for Kurdish youth both in the Diaspora and Kurdistan who want to get involved in journalism and/or politics?

Thirty years ago I might have given a different answer. My advice to the younger generation today is to do all they can to have an aim in life and to pursue that aim with discipline and determination. I would advise them to pursue a profession they like, a profession that can secure a job for them and guarantee progress both financially and professionally. Today’s circumstances also require people to be multi-skilled and ready to change professions. In today’s world the first university degree may not secure you a good position. Individuals may have to do a second degree or postgraduate degrees.

For the youth in Kurdistan I would hope they would contribute to a more advanced style of journalism to inform and enlighten their listeners/audience. We need journalists who can find methods enabling them to deal with many social issues and taboos within the Kurdish societies. I would advise them to put an end to the methods aiming at brainwashing people directly or indirectly. We need journalists to make the Kurdish people feel they are a part of the world, hopefully the advanced world, a nation that wants to innovate rather than copy and imitate. The Kurdish people need journalists who can inform about all what is related to life, including issues related to education, economy, politics and employment, not just politics. Many politicians and journalists would like to continue with the trend of mid twentieth century and drum on awakening “the national feeling” and patriotism. I think we have done enough drumming that has now exceeded its need. I don’t think there is a Kurd any where who is not aware of his/her identity. Indeed we now have some who are close to being fascists without knowing. Recently someone has posted this in Facebook: “I hate the Arabs and if that makes me a facist I am proud of being a facist. Long live Kurdistan.” That made me sad but what made me sadder was the fact he has written that in Arabic because, although living in a European country, he was still illiterate in Kurdish. His mentality was no longer the mentality I know that used to be Kurdish. It was the mentality of a fanatic baathist or or a Turkish kemalist facist.

In Kurdistan, especially amongst the Kurmanji Kurds, One of the biggest disadvantages people have is illiteracy. As writers or journalists writing in Kurdish we are facing a wall because we cannot communicate with the masses. The mentality of many Kurds today is much closer to the Turkish, Arabic or Farsi mentalities because it is the language that plays the most important role in developing the individual’s mentality.

The Kurds of today need institutions, writers, educators and journalists who can show the new generations better ways of thinking, smarter methods in dealing with life and politics and more useful, relevant and realistic approaches in regard to the struggle for national and cultural rights.

As far as the Kurds in the diaspora are concerned, in a place like Australia, or in Europe, journalism by itself may no longer guarantee you a satisfying good job. You need to have other skills and qualifications in addition to your degree in journalism. If someone wants to become a journalist I would advise him/her to think again if the the aim is to just use journalism as a tool “to serve the Kurdish cause.” These are outdated and often unrealistic aims not relevant to journalism in the advanced countries. Although enhancing and publicising causes are still possible, more subtle methods and support are needed to do so. Nowadays issues such as balance, objectivity and fair reporting are the trend, and your employer, certainly establishments such as ABC and SBS, would expect that from their employees. As a journalist you cannot publish anything you like without the agreement of the editor of whoever you are writing for.

In regard to becoming involved in politics, I would like to make the following remarks:

The Kurdish people are over politicised and many are brainwashed either directly or indirectly, often without knowing. There is too little objective thinking, too little individualist approach and too little freedom of expression amongst the Kurds themselves. The political organisations and the society itself are against individualism and radical change from what they consider to be the norm. If an individual wants to become a politician it depends where that individual is. In Kurdistan he/she would have to be a member of a party and the party would expect him/her to be totally “loyal” to the leader and the party. Some parties may allow limited criticism while others may turn you into a robot or a puppet. We need a generation of politicians not to be against the establishment and the present status quo merely to antagonise them but a generation of politicians who aim at improving the way of thinking with the aim to salvage Kurdish politics from the political mentality of the fifties and the sixties. Such politicians need to be equipped with super skills in order to make change possible without bloody revolutions or civil wars.

The Kurdish people have various choices: To imitate the Arab countries, to follow the model of the Islamic countries such as Iran, to go in the same direction as a country like North Korea, or still worse Somalia and Afghanistan; or to follow in the steps of advanced democracies where free thinking, mutual respect and intellectual awakening are a reality. If the latter is the preference then hard work, planning, group-work, discipline and cooperation is needed, all of which are lacking amongst most Kurdish societies today. The new generation of politicians need to vitalise a machine that can create those requirements in order to overcome political and social corruption, internal hostilities and decayed political and religious ideologies. A new ideology is needed that can organise peaceful and constructive struggle to secure the legitimate rights of the Kurdish people in the country they are in at this stage.

The Kurdish youth outside Kurdistan need to become a part of the political process in the country they live in. The Kurdish people in Kurdistan do not need another one to shout, “Long live the leader.” They need some sort of a different contribution, something they themselves lack.

Look at the Kurds in Australia, for instance. We don’t have a single high-ranking politician from Kurdish background. We may find parliamentarians, in some cases ministers, or successful business people of Italian, Greek, Armenian, Arab and Assyrian backgrounds but I am not aware of one single high-ranking politician or millionaire of Kurdish background. If I take myself as an example, I put the Kurdish stamp on myself from the day I arrived here and my entire political life was wrapped around Kurdish politics. I lost many opportunities that could have opened a road to a successful career in Australian politics for me. I regret nothing and that might have been a natural way to go for someone like me that belonged to another generation and came here in different circumstances; and I am proud of my humble achievements, but my advice to the younger generation of Kurds in the diaspora is this: Be successful in the country you are in, become a politician in the country you are in and act as a citizen of that country, but never forget your background and remember that the Kurdish people belong to the most oppressed in this world; they need your and everyone else’s support. Remember that a person who cannot guarantee success and happiness to himself will never be able to raise a happy and successful family, and someone who fails to offer himself and his family happiness and success cannot help the Kurdish people. Saying “Long live Kurdistan” or “Long live my leader” one thousand times a day will do nothing for anyone if you and your family are neither happy, nor successful. On the other hand, even if you don’t directly contribute to the Kurdish cause, raising a happy family with successful members is by itself a great service to the Kurdish people in one way or another. We should remain loyal to our people and our motherland but we also need to be loyal to the country we now live in and where our children will grow up. It is essential to contribute to the well-being of our new country so we may play a role in its presence and future.

What is your view in regard to the future of the Kurdish people, the Kurdish politics and Kurdistan?

The Kurdish people in general are changing and it is no exaggeration that they are progressing in some respects faster than their neighbors. The majority of the Kurds are religiously less fanatical, they are more tolerant and adapt to change faster. But on the other hand a big gap is beginning to appear between the educated/ politically advanced individuals and the masses. On one hand you have amongst the Kurds of today those who comprehend world politics, are capable of working even with governments and organisations outside Kurdistan and on the other you have those who have not developed the capacity to think individually and analyse objectively. The latter group is deeply influenced by opinions made by others and sometimes fanatically supportive of them without in-depth comprehension.

In the eighties and nineties in my political writings I portrayed the idea that the Kurds had a common faith and thus needed a common strategy/struggle based on national unity. By 2000 I realised that we were stubbornly ignoring the reality of our situation and thinking with our hearts rather than using our brains and logic.

Regardless of what many of us feel about the unity of the Kurds and Kurdistan the reality is neither the Kurdish people, nor their country, are/ were fully united. Kurdistan is a vast region extending from areas close to the Mediterranean in the west to Lake Urmia in the east and from Mount Ararat in the north to areas close to the Persian/Arab Gulf in the south. Because the Kurds speak a variety of dialects, some of which are considerably different, and due to factors related to different alphabets, and because their children are influenced by differing educational systems; add to that the segregation imposed for centuries by natural boundaries and the geopolitical factors, we now have not one but various Kurdish cultural and political mentalities. The circumstances in each part of Kurdistan are different from the others. The strategy needed for the realisation of Kurdish rights in Syria is totally different from those in the other parts. Therefore it is only logical to realise that the Kurds in each part need to develop the best strategies that suit their situation, their circumstances and the reality of the politics in the country they are currently a part of. As I suggested in some of my articles many years ago, there is an urgent need for a body, let us call it a congress, in order to develop ways that would bring the Kurdish people together and create some sort of coordination between the organisation of all parts of Kurdistan. One would hope that the members active in such a body would gradually consist of academics, linguists and specialists that have qualifications and skills to develop programs and practical methods such as those that would contribute to the formulation of a standard written Kurdish, rather than members representing political organisations, some of whom may have nothing more in mind than having an extra seat or greater influence. The Kurds need to realise that without developing a standard format of written Kurdish no real unity would ever be possible, for real unity does not lie in two or three Kurdish political parties forming a front but in a Kurd in Mahabad reading and understanding the same newspaper that is read and understood by the Kurds in Diyarbekir, Hewler (Erbil) and Qamishli. The future of the Kurdish people therefore is dependent on how realistic the Kurdish people can become in comprehending the real situation and circumstances where-ever they may be and how their political organisations develop strategies that can function and achieve successful results in those situations and circumstances.

Something that is extremely important for the future is the necessity to desert the idea that only armed struggle can guarantee Kurdish rights. The Kurdish proverb “only the force and the rifle have the solution” (Zor zane, devê tifinga more zane) is no longer valid. There are already signs the Kurdish movement in general, even an organisation such as Kurdistan Workers Party, PKK, are realising this. While many Kurds have a love affair with the sound of the gun and are proud to see someone fighting the enemy somewhere, let alone the adoration of a picture portraying young woman or a child carrying a Kalashnikov, in todays circumstances any form of armed struggle is nothing but harmful to the interests of the Kurdish people in one way or another. Historically armed struggle has brought nothing but devastation and death to Kurdistan and its people. History books are full of examples. What the Kurds of today need is not fighting but a more relevant national awareness, educational progress and strategies that can develop practical means for a peaceful but consistent struggle for equality, national identity and economical progress. The Kurdish people are in desperate need of bidding farewell to some of their habits, including political tribalism.

The Kurds. If we exclude the Kurds in the former Soviet Republics and those inhabiting urban centers in the Middle East or elsewhere, live in four countries: Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria. The borders of these states divide Kurdistan and each part has different circumstances and conditions. If one has to talk about the future of Kurdistan one needs to look at each part separately. One cannot analyse the current situation or what is needed for the future Kurdistan by giving southern Kurdistan as an example, for instance. By now each part has its own history and different needs and expectations. What is going on in the Kurdish regions of Syria, for example, is unique and often misunderstood by the Kurds from other parts who lack firsthand knowledge and are simply influenced by propaganda and their national sympathy, without even being aware that the three Kurdish regions in Syria are not attached geographically. The analysis needed for the future of these regions is completely different from one that would be needed for the Kurdish regions in today’s Iran.

One has to add that the future of Kurdistan in general is also dependent on the political mentality of the Kurdish organisations, many of whom are still dependent on theories that come from the era preceding the Soviet Union. Some may even still harbor Stalinist tactics. These organisations need to liberate themselves from such tendencies and adopt real democratic principles within the party apparatus and in dealing with the people should they expect a brighter future. As mentioned before, the future of the Kurdish people is also dependent on the individual’s ability to become more capable in his/her way of thinking and the society becoming more creative and achieving. The Kurds in the diaspora could play a role in this direction provided they give something new and valuable to their people rather than importing political tribalism from their original country.

In brief the Kurdish people everywhere need to realise that often a small gain is not only an accomplishment but also a step towards greater achievements in the future. Struggling for an independent Kurdistan, let alone the Greater Kurdistan, sounds wonderful but could last decades or even centuries to realise if at all, and the road to such an achievement could be full of more wars, more destruction of our country and more death and misery. The struggle for smaller aims could be a smarter way towards the same aim but without bloodshed and destruction. Thinking even more optimistically, when people of different national and linguistic backgrounds develop an attitude of mutual acceptance and respect the necessity of separation may no longer be required. If the European Union succeeds in uniting Europe after so many wars that caused so much death and destruction, why couldn’t such an aim become a reality elsewhere one day. After all only ten years ago the Turkish leaders used to label Masoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani as “tribal leaders” and “war lords” when today they have red carpets ready for them when they visit Ankara, whatever the reason.

During your work as a broadcaster/journalist, what influential people have you had the pleasure of interviewing?

In more than 30 years I have interviewed hundreds of people from Kurdish leaders to intellectuals, from singers to ordinary people, as well as many from other backgrounds in relation to issues relevant to the Kurdish cause or people.

In the eighties and nineties it used to take me a lot of effort to locate and interview Kurdish leaders but they never refused to be interviewed by me, even though occasionally I had to spend sleepless nights chasing them all over the Middle East, the USA or Europe. I always looked forward to interview Kurdish leaders but interviewing them was not without frustration. Kak Masoud’s answers often consisted of one or two sentences, so if you had four questions prepared he could have answered them all in less than two minutes. You had to quickly search your mind for additional questions. Mam Jalal, on the other hand, often talked for twenty or more minutes before you had the chance to ask the second question, while Apo (Abdullah Ocalan) would need at least half an hour to make propaganda for his party and accuse others of being fascists, feudal chiefs or reactionaries.

The Kurds are mostly very serious people but I did enjoy interviewing most of my guests. It used to be fun talking to the Kurdish journalist/writer, the late Mahmoud Baksi. While Nasir Rezazi was OK to interview on any subject, an interview with Shivan Perwer often included controversial subjects due to politics or his problems with a particular organisation.

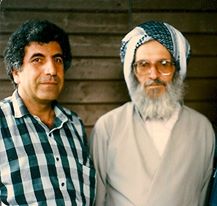

I cannot remember all the interviews I conducted but I did enjoy interviewing Mr Ibrahim Ahmed (London: October, 1986), the secretary of DPK-Iran Abdullah Hesenzade (Sydney, September 1998), Hejar Mokriyan (France: October 1989) Merziya (Sydney: April, 1997). It was also pleasure to interview personalities such as Sherko Bekes, Kendal Nezan, Dr Najmaddine Karim, Peter Galbreath, Joe O’Sullivan, Gareth Evans, Hemresh Resho, Adnan Mufti, Nechirvan Barzani, Barham Salih and hundreds of other dear interviewees, including people now ministers in Iraq and Kurdistan and many members of the Kurdish community in Australia.

I know you do a lot of writing and have had your work published, what inspires your writing?

I had the desire to write early in my life and my first lines of poetry were in Arabic and German, later also in English. As with almost all of the Kurds of my time in Syria I was illiterate in my mother tongue. Although we spoke Kurdish in the Kurdish regions the teaching of Kurdish was forbidden. I taught myself how to read in Kurdish after my arrival in Europe. In Australia I improved my skills by subscribing to Kurdish magazines that were available in Sweden in the late seventies and early eighties and by reading literary books. Studying subjects dealing with German literature and English linguistics contributed to my skills as a writer.

Writing in Kurdish was a necessity for me. There wasn’t much available in Kurmanji in those days and the material available was limited as far as the content was concerned. I thought my experience as someone who knew his mother tongue very well, spoke various languages, lived in Europe and Australia and had first hand contact with German and English literature might assist me in giving the Kurdish library something new. There was also a political need as far as I was concerned. I thought I could come up with some sort of alternative to what was mostly written in the late seventies/ early eighties about matters relevant to Kurdish politics.

My early poems and short stories were more patriotic compared with my latter writings. I guess I needed some time to rid myself of the propagandist style most of the Middle eastern writers are influenced by or attached to, I needed time to mature as a writer and become more objective in my approach to the subjects I chose to deal with. I must admit, however, being of Kurdish background keeps on drawing me to the Kurdish scene. Regardless how much one desires to free oneself from the strings of Kurdishness one is drawn to the swamps of Kurdish politics. The oppression by brutal governments, the fighting amongst the Kurdish organisations, the mistakes and the brutality committed by some Kurdish parties along the way, the disadvantages our people suffer from, all keep on pulling you to that swamp that at times nearly drowns you. There were periods in my life when I longed for becoming an Australian citizen fully committed to my new identity and to become more active in Australian politics that earlier had offered me more than one chance to climb the political ladder but again and again my Kurdishness pulled me back. After spending nearly 45 years in Australia I am still swimming up to my neck in the Kurdish river. Not a day passes without writing one, two or ten pages in Kurdish, excluding what I write for the Kurdish program on SBS Radio, and not a day passes without being influenced, pleased or annoyed by something that is going on in one or another part of Kurdistan. It seems the first fifteen years of my life had a very strong affect in formulating my destiny although that destiny took me through roads I never dreamed of following when I was a kid in a Kurdish village.

As a writer what torments me, like many others who write in Kurmanji, is the limited number of readers. Sometimes I feel so sorry for myself. Some of my writings, especially my novels WENDABÛN (Getting Lost) and VEGER (The Return) are works not of lesser quality than a good work in any other language but our people are mostly illiterate and those who can read do not like lengthy and complicated works. Many times I had the desire to stop writing in Kurdish but again and again my conscience made me continue. I convinced myself that if only 50 people read what I wrote it was better than not to write. I encouraged myself by hoping maybe my writings would somehow positively influence some readers, and some readers do give me that impression, and maybe they would be more appreciated by future generations.

Currently the Kurdish Regional Government in southern Kurdistan is the biggest accomplishment the Kurds have, something that eventuated from a historical opportunity. Although that opportunity could have been used much better, nevertheless it is the only thing close to independence the Kurds have had. Holding to what is at hand there and advancing the aims and achievements could be a matter of life and death to that part of Kurdistan and to the Kurds in general.

The future of the Kurds in Syria is in the fog right now. I would rather not go into the details except to express my concern about our people there who are going through a very difficult time. Let us hope they can escape the dark storm all of Syria is going through right now.

If you had the chance to do something differently, what would it be?

Once I would have said “To become a freedom fighter in the mountains.” In my earlier writings I encouraged the youth do do exactly that but times have changed, so have the circumstances and my perception of politics. As a writer if I could go back, I would have written and published more in English.

If you want to know what I would have done if I had a lot of money today, I would have organised a special course and given gifted young Kurds the chance to come to Australia for six months to attend that course that would deal with modern politics and the freedom of thought and expression. Other than that I would have opened a modern Italian Café on a lovely beach.