A question that floats in the minds of those who are foreign to the Kurdish people and their tribal homeland is “who are they?”. The question of who we are and what we are has been the subject of great literature past and present. We’ve seen many rise and fall in their pursuit of understanding our origins with respect to geography, culture, language, heritage, ancestry, etc. What we have available from ancient times is recollections of personal documentations of Kurdish principalities (Şerefname), poems by leading men and women, and the legacies of dynasties of prominent Kurdish leaders under the banners of oppressive empires.

A more modern interpretation of Kurdish history, which reflects on ancient knowledge, is the poem “Kî ne em?” by the great poet Cigerxwîn. The rhythm, rhymes and play on words are wrapped around known historical facts that portray not only the struggle and oppression of Kurds, but also make historical references to Kurdish origins and modern references to this nation.

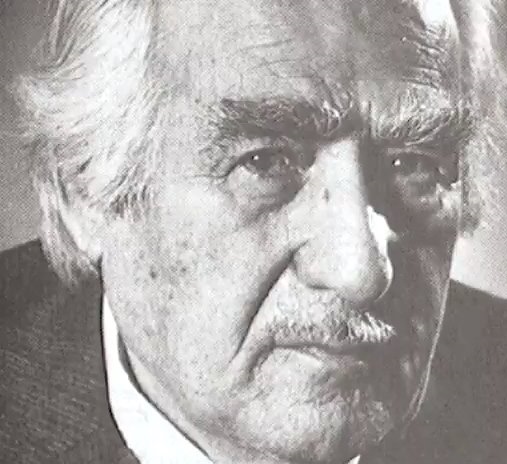

Under the alias of Cigerxwîn, Şexmus Hesen/Sheikhmous Hasan is a living poet in Kurdistan well after his death. His poetry is a staple of modern Kurdish literature and has become inspiration for modern Kurdish writers. It is commonplace in Kurdish literature to make reference to his ideas, thoughts and ideology on Kurdish nationalism. Influenced by past literature himself, Cigerxwîn commonly made reference to ideas used in existing Kurdish writings with his own interpretations of the significance of the written words.

A very significant aspect of the Kurdish identity and frequently mentioned within Kurdish literature is the festival of Newroz. Newroz, for the Kurds is more than a celebration of the Northward Equinox. It is deeply rooted in mythology, dating back several centuries, and has become the representation of the fiery Kurdish spirit. Writers in all forms of Kurdish literature make reference to Newroz as a way to re-ignite patriotism within the readers’ heart and mind.

“Who are we? We are the makers of Newroz; once again we shall become our own masters, the rulers of our lands, so that we may enjoy the fruits of our orchards, relish the sacred wines of our vineyards, and put an end to a dark era by seeking salvation in knowledge and science. We shall make another new day and breathe the pure air of liberty.”

With the introduction of the symbol of Newroz, Cigerxwîn uses poetic allegories alongside the symbol to emphasize his point. His claim being, as the makers of Newroz, we are capable of once again bringing about a new day to our gloomy dark reality. This style of incorporating the symbol of Newroz reigns true amongst an endless list of Kurdish writers. Newroz within poetry and literature as a whole is introduced as a beacon of hope. This is the emotion that is being provoked in this particular stanza. He writes, with the coming of Newroz we will once again become “rulers of our own land” and as its’ blaze lights our days we will “put an end to a dark era”. Towards the end of the stanza, he concludes that in order to bring an end to all the oppression and finally relish in the light of freedom, Kurds need to turn their paths towards greater enlightenment through education (which one could further implore would create “free-mindedness”).

Similarities are quite often made between the persona of Kurds and king of the jungle, the lion. Not only specific to Kurdish mythology, but throughout Eastern mythology, the lion was seen as a very majestic creature that represented royal dominance. Often the phrase “The Lion of Kurdistan” is used within Kurdish literature – similar to the symbol of Newroz – as a literary tool that is meant to arouse patriotism. “Proud as a lion” is a very significant phrase because it holds a lot of power behind it, and through the following stanza Cigerxwîn tries to make apparent the power of the Kurdish nation:

“Who are we? The children of the Kurdish nation awakened from deep sleep. Marching forward, proud as a lion wanting the whole world to know we shall struggle and continue the path to freedom. We shall learn from great men. We make a vow to our ancestors, to Salar, Shergo and Deysem, that our resolve will remain vigorous, unyielding, and stronger than death. Let it be known, we announce with no fear, liberty is our goal and we shall advance in this path.”

Drawing on the power of the persona of the lion, he declares that the Kurdish resolve is “stronger than death”. This bold statement is significant because Cigerxwîn is not only trying to illustrate the strength of the Kurdish nation, but is also provided as a reminder to the generations that have been and are being exposed to his poem. Yes, he deduces, “we shall struggle” but also “continue the path to freedom”.

Nature is a very popular theme used as symbolism throughout Kurdish literature. Artists from poets to photographers capture nature to depict Kurdish culture, because it’s become embedded into every aspect of the Kurdish identity. Nature has a significant role within the Kurdish culture mainly because it is the physical representation of our identity. It is what connects us to the land we have adorned with our existence for thousands of years. From Hurrians, to Medians, to fragmented principalities, we held onto the soil that – many a Kurdish poet has written – we have watered with our blood. The introduction of the poem draws on this very theme:

“Who are we? Kî ne em? Who are we, you ask? The Kurd of Kurdistan, a lively volcano, fire and dynamite in the face of the enemy. When furious, we shake the mountains, the sparks of our anger are death to our foes.”

The poetic language used from the get-go is typical. It becomes clear that the intention is to make the Kurd synonymous with his surroundings, essentially making him part of the land he makes a declaration of claim to. Why? Seems a bit excessive to assert such ownership on the on-set? Realistically, it’s become embedded in the poetic language of Kurdistan to include such declarations within literature. Reason being for centuries the claim to Kurdistan was recognized to a degree, but was never solidified into a geographic reality. There was recognition of Kurdish principalities under large Middle Eastern empires, but never a known Kurdish state. So therein lies the need for Kurds to make clear their desire for statehood decorated with poetic language.

The poem then concludes with a befitting message to a patriot Kurdish heart:

“Bijî Kurdistan, bimir e koledar!/Long live Kurdistan! Death to the oppressor[s]!”

Access the full poem here: http://kurdistanspastisprologue.wordpress.com/2012/10/10/kine-emwho-are-we-cigerxwin/