The foundation of the modern Kurdish identity is stitched together by the poetry of bleeding hearts. We, as a suffering nation have been kept alive by our unyielding desire for freedom and universal equality. It was our nation that kept others afloat from total annihilation by foreign powers, but ironically we have we’ve been sent to the guillotine by those we’ve saved.

Albeit we lacked outside support, our communal characteristic for change kept us alive through lyrics, metaphors and similes, poetic lines and stanzas. The poetry of the bleeding hearts ignited our will to preserver amongst the inhumane oppression and continued violations to our existence.

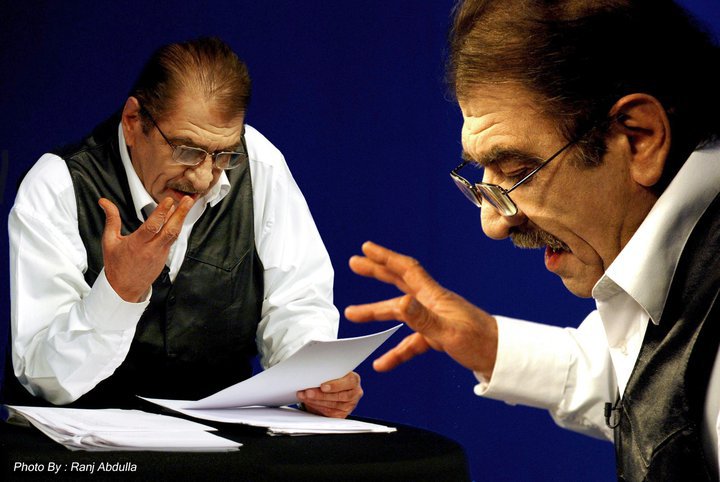

One such bleeding heart was Şerko Bekas. Born in Slemanî in 1940, he was immersed into Kurdish literature from the onset, being the son of the renowned Kurdish poet Feyak Bekas. Mr. Bekas Jr wrote for the struggle of his nation. His writing’s became home to popular themes within Kurdish poetry and this translated well with his readers. His aim, from what has been observed from his work, was to bring the plight of Kurds to the attention of those who were foreign to their centuries-long oppression.

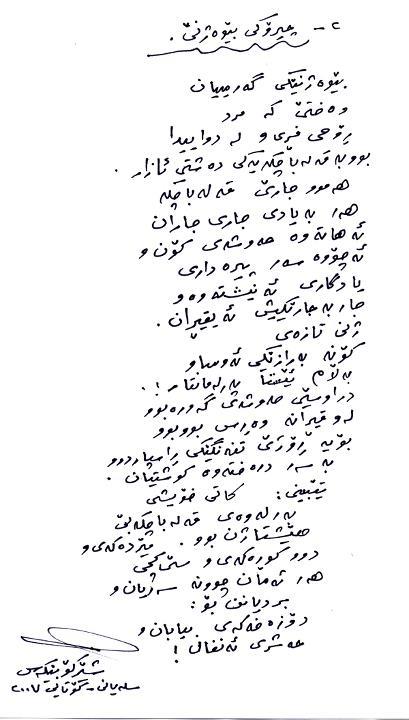

His piece entitled, “A letter to God”, was written after the chemical attack on the town of Halabja. Each stanza is a plea for recognition of the suffering of the Kurdish nation. But from one messenger to the next, the plea was ignored and finally rejected as is illustrated in the following exerpt:

a carried pigeon asked me,

“okay well, who’s going to send it for you?

don’t expect me to.

I cannot fly that high to reach God.”

Such was and is the continued reality of this nation. The poem seemed to have almost a satirically element in its message. The object of ridicule is the lack of empathy from those who are made aware of the Kurdish situation. Those who are enlightened with the suffering of Kurdistan seem to abandon the burden of the Kurds.

Aside from bringing the suffering of the Kurdish nation into the international arena of recognition, Şerko Bekes also was a proponent of awakening the Kurdish nation as well as demonstrating to those with murderous aims, the undying Kurd. “Seeds” is one such example that represents the anguish but also the triumph of Kurds.

We were millions

we were old trees

newly growing plants and seeds.

From the helmet of Ankara

they came at dawn

they uprooted us

they took us away

far away.

The nation of young and old, Bekes writes was indiscriminately displaced from their homeland into areas foreign to these mountaineers. The poem has an introduction empty of hope, it tells the tale all too familiar with Kurds. But it does not stagnate with this depressing story, as seeds do, it blossoms into one that truly reflects the Kurdish spirit:

We had seeds

carried back by the wind

they reached the thirsty mountains again

they hid inside rock clefts

the first rain

the second rain

the third rain

they grew again

Now again we are a forest

we are millions

we are seeds

The survival characteristic of the Kurdish nation is very much embedded in Kurdish literature. It seems as though with every genocide and every oppressive regime, Kurds multiple. This is the spirit that had been planted by the poets and writers of Kurdistan. It has become a means of keeping the Kurdish nation alive despite the vengeful murders of hundreds of thousands of us. The end of this poem reads as follows:

Can you finish us off?

But I know

and you know

as long as there is a seed

for the rain and the wind

this forest will never end.

Unyielding, determined, at times staring death in the face: we are Kurds.

Sadly his is being laid to rest in an oppressed Kurdistan; however his work will pave the way for a free future for his people.